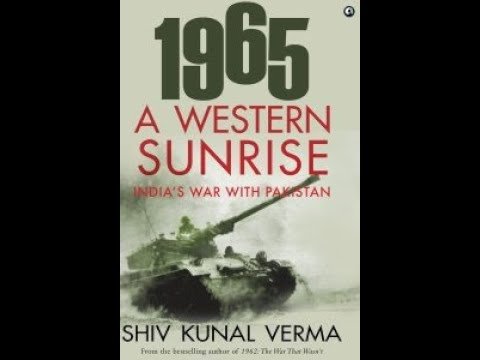

Maj Gen Jagatbir Singh on 1965: A Western Sunrise, in discussion with Writer Shiv Kunal Verma

A discuss with Maj Gen Jagatbir Singh on 1965: A Western Sunrise, with writer Shiv Kunal Verma . Shiv Kunal Verma, an acclaimed historian and filmmaker, has written an encyclopedic history of the 1965 India-Pakistan War, which began when Pakistan attacked Indian forces in the Rann of Kutch in April 1965, stalled as a result of a temporary ceasefire brokered by the British, and restarted in August when Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar by crossing the Ceasefire Line (CFL) into Indian Kashmir, and formally ended on 10 January 1966, when the Soviet Union mediated a peace agreement in Tashkent. The immediate dispute centered on Jammu and Kashmir, but Verma traces its genesis to British colonial misrule, religious differences, and Cold War geopolitics. “The fate of India—and that of Kashmir—had been sealed back in 1919”, Verma writes, when Britain’s India Office, the Colonial Office and the Admiralty prepared a plan to partition the subcontinent into Hindustan, Pakistan, and Princestan. Although officially rejected at that time by the House of Commons,

“the blueprint for the creation of Pakistan primarily to serve British interests in West Asia and to counter the Russian threat from the direction of the Pamir Mountains had been created, and … it influenced events thereafter.”

Britain’s plan to subdivide the Indian subcontinent between Hindus and Muslims, Verma believes, was in part, therefore, a legacy of the 19th century’s “Great Game” between Britain and Russia for control of central and south Asia. After independence and partition, the region became part of the larger Cold War struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union. The United States armed Pakistan, while the Soviet Union armed India.

Indian forces successfully resisted Pakistan’s August 1965 offensive into Kashmir, but Pakistan followed-up with Operation Grand Slam on 1 September, which pushed Indian forces back to Akhnoor and involved the air forces of both countries. Five days later, Indian troops crossed into Pakistani territory, finally turning from defense to offense. This was a decision made at the highest level of the Indian government by Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. For the next two weeks, the armies and air forces of both sides fought in Phillora, Khem Karan, Chawinda, and other places. The United Nations negotiated a ceasefire on 22 September, with the formal peace agreement signed four months later. The number of casualties on each side is disputed to this day, as is the war’s outcome. Both sides claimed victory, but Verma rightly calls it a draw.

Verma, whose father served in India’s military and who discussed the minutiae of combat plans and actions with Indian military officers, has an eye for detail. The book is replete with tales of company-level skirmishes, air combat dogfights, tank battles, paratroop drops, friendly-fire incidents, missed opportunities, inter-service rivalries, and intelligence failures. It is told from an Indian perspective, but Verma casts his critical eye on India’s senior military and political leadership during the conflict.

Verma is most critical of India’s Army Chief General Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri, blaming him for the failure to integrate the Indian Air Force and Navy into his war plans. He believes that General Chaudhuri should have been relieved of command after India’s disastrous failure in the war with China in 1962, and accuses Indian Defense Minister Yashwantrao Balwantrao Chavan of being more concerned with protecting then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s reputation than reorganizing the Indian military’s higher command. The hard lessons of India’s defeat in 1962 (the subject of Verma’s 1962 The War That Wasn’t) were simply ignored by India’s leaders—both military and political. Indeed, throughout the book, Verma repeatedly criticizes senior Indian military leaders, but couples that with effusive praise for the junior officers and combat troops who enabled India to resist multiple Pakistani offensives.

Most of Pakistan’s military and political leadership fare no better in Verma’s book. Pakistan was better equipped (mostly by the United States) and had the advantage of often choosing the times and places of battles, but frittered away those advantages due to incompetence, the fog of war, and stubborn resistance by Indian troops.

In the end, the war settled nothing. Six years later, India and Pakistan would clash again, and that war, too, resolved nothing. The enmity between India and Pakistan continues, but now both sides are armed with nuclear weapons and are caught up in a competition for Indo-Pacific primacy between the United States and China.

Francis P Sempa is the author of Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century and America’s Global Role: Essays and Reviews on National Security, Geopolitics and War.